How LLMs Work: Stages 0-3

Intersecting AI #3

LEAI mostly focuses on Generative Artificial Intelligence. Large language models (LLMs) are the type of AI models that power GenAI technologies like ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Llama, and others.

At a high level, LLMs find the statistical relationships between words and sentences, then output sentences that have a high probability of sounding like they make sense. Image generators have a similar process; they find the statistical relationships between images and text and blend them to create an output that is highly likely to match the requested input.

Perhaps at this juncture it’d be beneficial to understand how these LLMs work so we know exactly what we’re talking about and how it intersects with big legal and ethical questions.

Stage 0: Data Creation

This stage is typically not a primary role of AI entities.1 Rather, it’s where content creators come in: musicians, voice actors, coders, writers, photographers, people who post on social media, artists, directors, and so on. If you created any type of content and put it on a public part of the internet, or allowed it to be put on a public part of the internet, or someone else put it on a public part of the internet whether you wanted them to or not, then you have created raw training material for AI. And even if you put it on a private part of the internet (like if you wrote a Facebook post with limited sharing settings), the platform might still be using your data to train its own internal models or selling your data for training by other companies.

Stage 1: Data Collection

The initial step to data collection is to gather all the data you can possibly obtain. This involves accessing and retrieving content on web pages. The content is data. This first step is crucial because a model is only as good as the quantity and quality of its data.2

For LLMs to work they need oodles of data. Gobs of it. Loads, even. The more data, the greater the statistical analysis. Think of it like the law of large numbers. It's not remarkable to flip a coin 10 times and get heads 8 times. But it'd be highly unlikely to flip a coin 10,000 times and get heads 8,000 times.

Similarly, when the model is learning connections between words and phrases and concepts, the more data it draws on, the more useful the result of the analysis because it will have a chance to observe lots and lots of rare patterns and because it will be less likely to reflect pure chance or coincidence.

However, we can't just have more data without a diversity of data. For example, you can't train an LLM on just 10 billion copies of the same poem. All it would learn is how to reproduce that poem exactly. It's better to have 10 billion different poems. This is because human language is complex and to get an accurate statistical estimation of it, you need to include a lot of it.

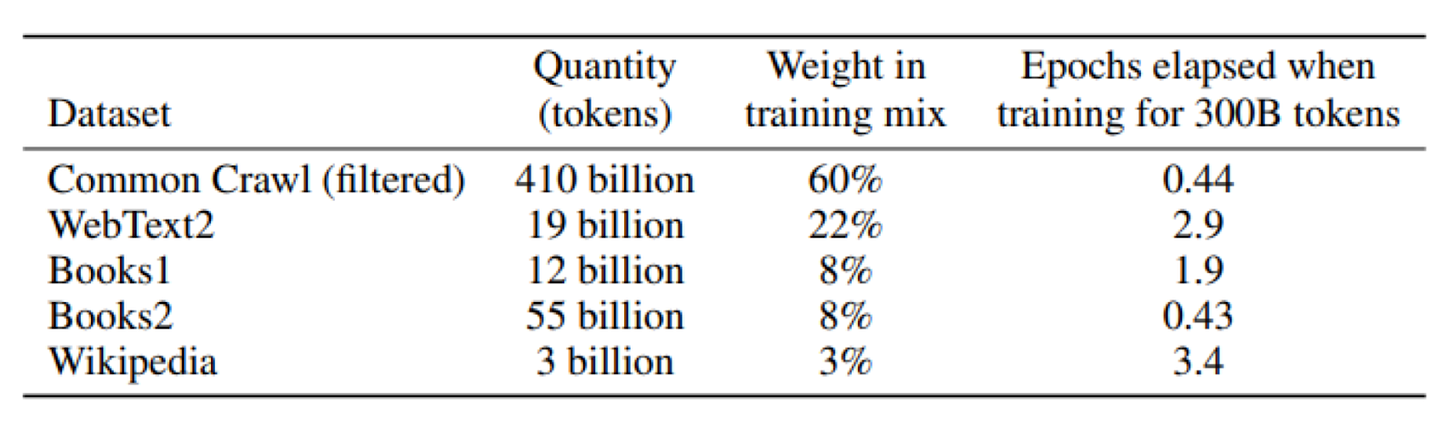

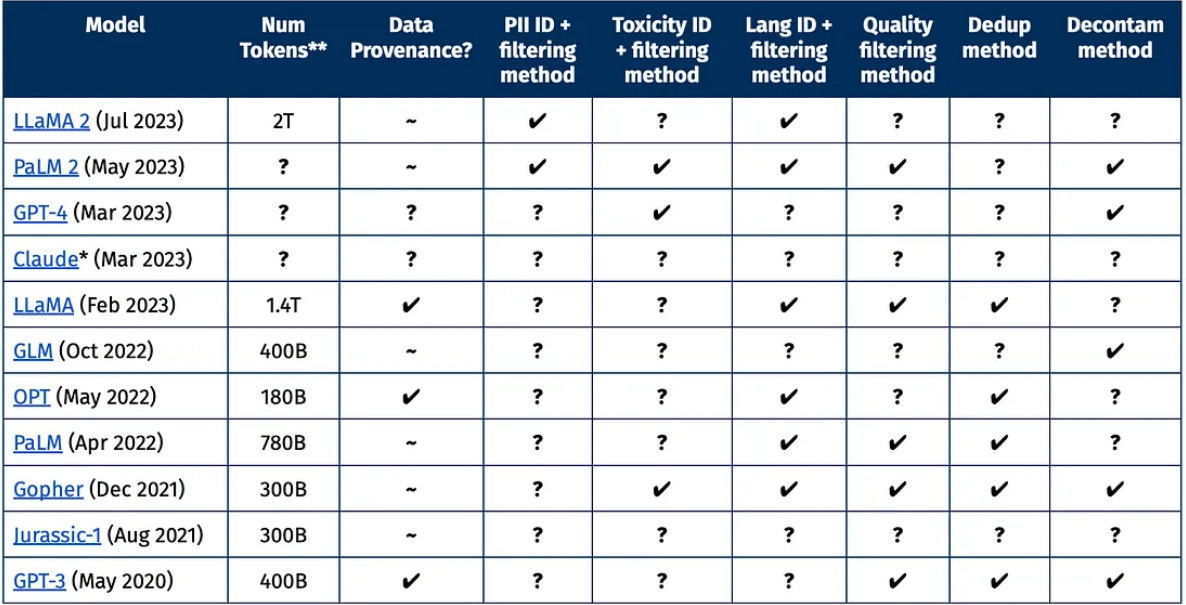

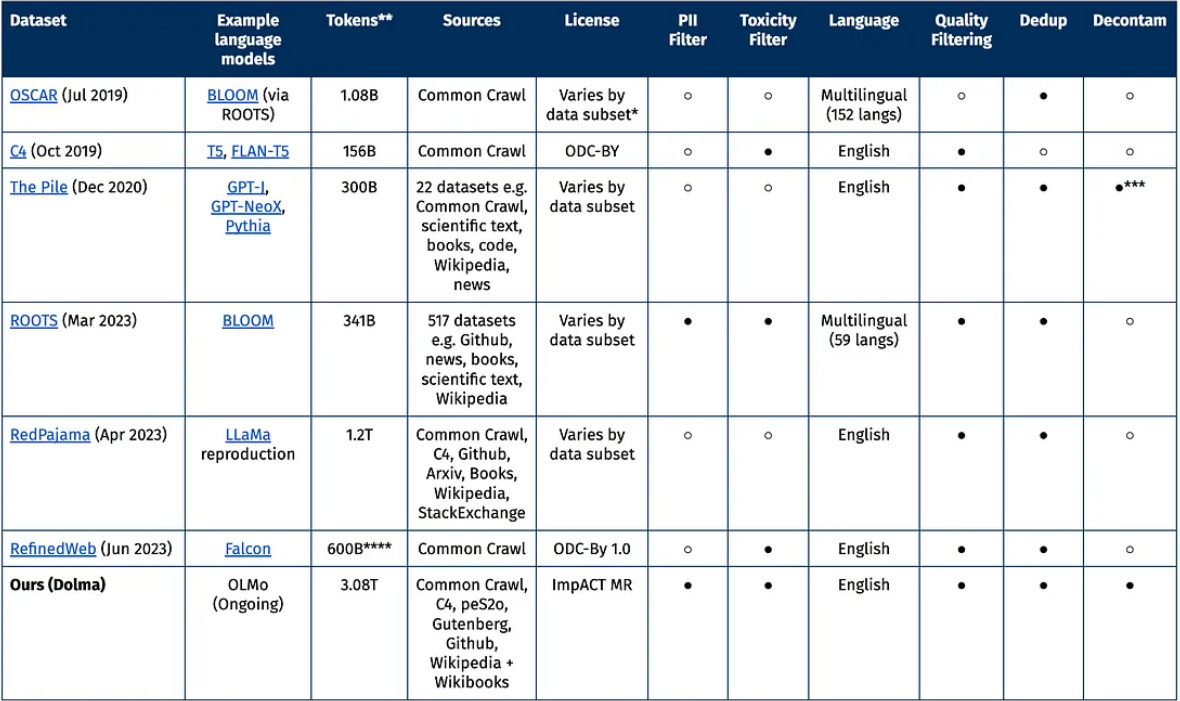

To give a sense of the scale of data needed to make decent models, GPT-3 (the precursor and less useful sibling of ChatGPT), was trained on about 5,000 times more words than the average child is exposed to by age 10. The datasets in the table below are those that GPT-3 trained on.

Importantly, the amount and quality of data is by far the most important element of high quality LLMs. The GPUs and algorithms different companies use are more or less the same, but the amount and quality of data isn't. All else being equal, better data is more significant than including more parameters or compute. This will likely remain true until there is some significant breakthrough in algorithms that allows LLMs to learn more from less, or learn to reason so that it doesn't need to see all information in order to discover it.

So where does all the data come from?

Developers acquire training materials (books, articles, photos, songs, etc.) for AI Models from a variety of sources, including:3

Public web crawling: Much of the text data for training large language models comes from web crawling and scraping. Companies, governments, nonprofit organizations like Common Crawl, and academic researchers crawl the web and scrape what it crawls to collect web pages, online books, and other texts. These datasets are then processed and made available to AI developers.

Corporate collections: Large tech companies like Google, Microsoft, and Meta have internal teams that work on scraping and processing huge amounts of data from the web and other sources to produce training datasets. Google has scanned hundreds of millions of books from libraries and converted them to digital form suitable for AI training, for example.

Public domain books: Some Training Materials come from public domain books, like those available via Project Gutenberg. These provide a source of older texts where copyright is not an issue.

Research datasets: Researchers release datasets that they have collected to advance AI research. For example, the BookCorpus dataset was created by academics. Google Researchers released the C4 dataset derived from Common Crawl data.

Purchased datasets: For some parts of the AI training process, companies may pay humans to produce example data. For example, companies may pay to create example dialogues that are used to fine tune a general purpose generative AI to perform like a ChatBot. Purchased data is typically small and built for a specific purpose. Companies are also pursuing data partnerships with organizations with lots of data, so "purchased data" is both data created specifically for a customer as well as licensed and potentially exclusive access to private, curated datasets.

[What follows is what we’ll call an aside. Information presented in the following format is interested or related to the topic at hand]

Consent and Alleged Data Laundering

It is important to note that currently much of the data collected and used to train LLMs is done without consent and without attribution. The fair use and copyright laws in the US have yet to specify the legality of using non-commercial data to train a commercial LLM.

This ambiguity has led to several instances of less-than-ethical data utilization by leading AI companies. A prominent example of this is the MegaFace dataset which was trained using the images uploaded to Flickr.com, an image hosting site. Researchers at the University of Washington utilized 3.5 million pictures that included Flickr users' faces, including over 670,000 people, without consent.

The MegaFace dataset was then used to build the AI facial recognition model that powers Clearview AI, which is a surveillance tech company used by law enforcement, the US Army, and the Chinese government. Flickr users had no option to opt out of this and were never informed about this use of their public photos.Stage 2: Data Curation

The curation stage is where the data (content gathered from various sources) is turned into information that these specific models can actually understand and process (i.e., model-readable, as opposed to human-readable, like the words on this page).

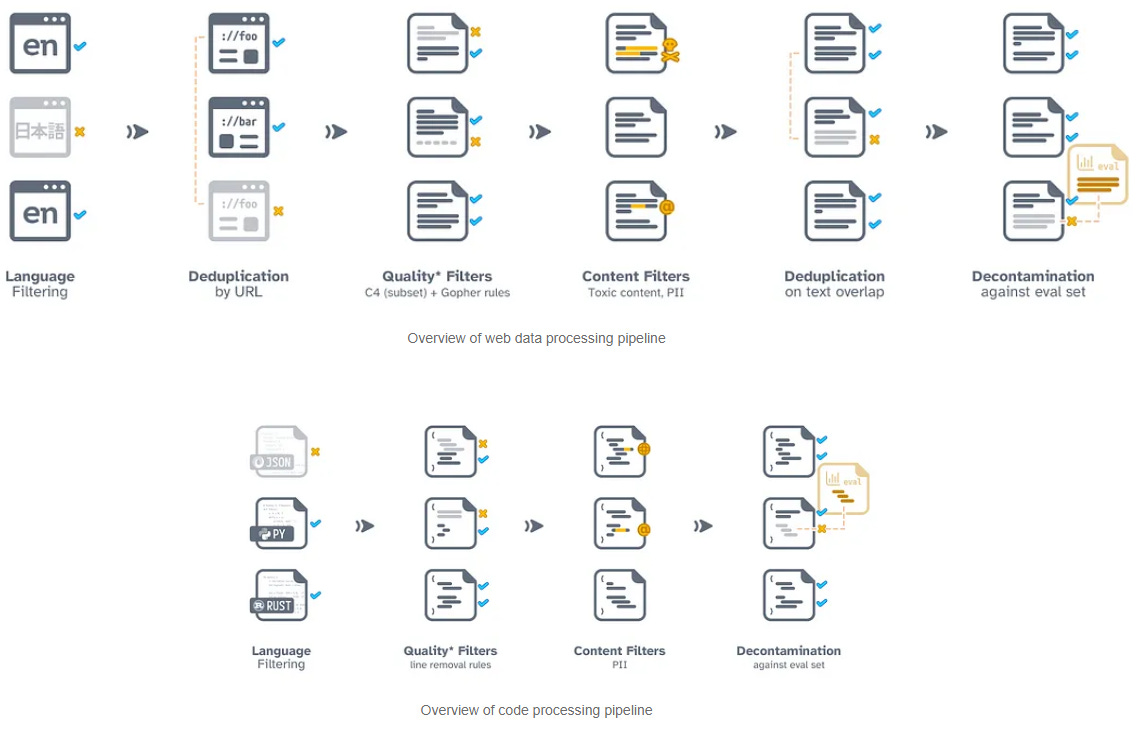

First, you take all the billions of documents you’ve collected in your training set and process it, which could include any or all of the following:

Individual document filtering to eliminate low-quality content, such as web pages that contain no or minimal text, or media that has severe OCR (optical character recognition- the process of converting a text image into a machine readable format) errors after digitization

Stripping individual documents of visual layout information, such as HTML, CSS, or document layout

Sections or whole documents may be removed due to several factors, including whether they are in languages AI developers do not intend to support (Arabic vs English), whether they are predicted to contain harmful or not-safe-for-work content (NSFW), or whether they are predicted to contain personally identifiable information

Collections are often de-duplicated to avoid multiple copies of the same document

The effect of these steps is two-fold. First, only a small fraction of the initial data is preserved (e.g., for GPT3, the original dataset was reduced from 45 terabytes to 570 gigabytes for training, meaning only just over 1% of the original data was retained for training). The various filters that are applied (like removing NSFW content) can be prone to errors and can lead to various biases in the dataset.

Second, training material is transformed to make it suitable for model training, but not for direct human consumption. For example:

Long documents may be split into shorter units that are easier for software to manipulate;

Aspects of documents useful for humans may be missing or may be altered for training (e.g., font style, section/chapter organization, headers/footnotes, diagrams/figures, etc.);

The reading order of documents may be changed.

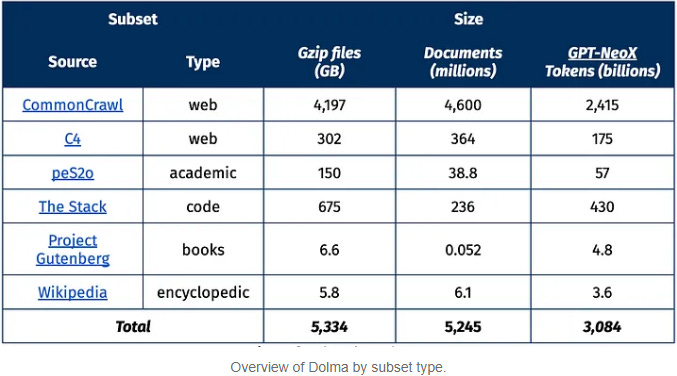

Processing Performed by AI2 for Dolma Dataset4

Dolma Compared to Closed-Source Datasets

Doma Compared to Open-Source Datasets

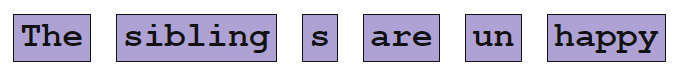

Tokenizing

Once the documents have been pre-processed and the training architecture is set up, it’s time to tokenize the words because a model is a specific type of software that requires input to be in sub-word chunks (tokens). Here’s an example of how one phrase is tokenized:

Becomes:

Notably, tokenizers are also trained models, but there's less work exploring them. Because of various biases in the tokenizer creation process, many underrepresented languages are split into more tokens than, for example, English, leading to disparate costs if using models like ChatGPT.

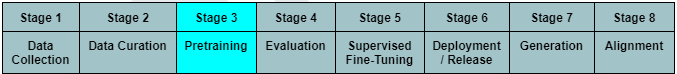

Stage 3: Pretraining

After the collected data is formatted for computers, it is then processed by training algorithms. During this step, the model learns about the word patterns in the data.

Vectors

The tokens, via the model, are transformed into lists of numbers (called vectors) that encode how that token relates to other tokens, which make all kinds of fancy computer computational magic possible.

Word vectors map words by contextual similarity. Words from similar contexts (e.g., "sunscreen", "swim trunks" and "towel") will be given values closer together than words like “camel”, “toothbrush”, and “book.” Furthermore, positional encoding ensures that the model not only learns how words are related, but also in which order they should appear. We know swimming and the beach are related, and we know you swim at the beach. You don’t beach at the swim. Or consider sleep:

I'm so tired; I want to sleep

He’s asleep on the job

She was sleepwalking last night

Let’s sleep on the bed

I sleep under the covers

She always sleeps throughout the night

They want to sleep on the long flight

All the associations of the word “sleep” with other nearby words are converted into vectors. Below is the vector for the word “happy.” It demonstrates the many, many associations “happy” can have relative to other words it’s found near in sentences and paragraphs. We don’t know what each number represents, exactly, but we do know that synonyms, like “happy” and “joyful” have similar vectors.

When given an input (that is, when a user asks the model to do something), the model internally constructs possible outputs based on the numerical relationship of words, then uses output that seems the most plausible.

From Ars Technica For example, here’s one way to represent cat as a vector: [0.0074, 0.0030, -0.0105, 0.0742, 0.0765, -0.0011, 0.0265, 0.0106, 0.0191, 0.0038, -0.0468, -0.0212, 0.0091, 0.0030, -0.0563, -0.0396, -0.0998, -0.0796, …, 0.0002] (The full vector is 300 numbers long—to see it all, click here and then click “show the raw vector.”) Why use such a baroque notation? Here’s an analogy. Washington, DC, is located at 38.9 degrees north and 77 degrees west. We can represent this using a vector notation: Washington, DC, is at [38.9, 77] New York is at [40.7, 74] London is at [51.5, 0.1] Paris is at [48.9, -2.4] This is useful for reasoning about spatial relationships. You can tell New York is close to Washington, DC, because 38.9 is close to 40.7 and 77 is close to 74. By the same token, Paris is close to London. But Paris is far from Washington, DC.

As mentioned before, word vectors ensure that each word is given a specific list of numbers that represent that word, acting like coordinates for the word. However, words can be complex and multidimensional, and in some cases, words can have multiple meanings. LLMs take this variation into account, giving each occurrence of the word a different value. For instance, the word “bat” can have two meanings, either referring to an animal or a piece of sports equipment, and these words are quite different in their meaning and context. Therefore, an LLM will assign a different vector to the word “bat” each time it occurs, taking into account the context in which it’s used.

The most powerful version of GPT-3 uses word vectors with 12,288 dimensions—that is, each word is represented by a list of 12,288 numbers.This process takes time and is compute-intensive. As the New York Times notes, “The largest language models are trained on over a terabyte of internet text, containing hundreds of billions of words. Their training costs millions of dollars and involves calculations that take weeks or even months on hundreds of specialized computers.”

Context Size

When building a LLM, the amount of processing you must do to turn words in a book into numbers a model can understand isn’t just dependent on how large your input dataset is. The size of the context window (aka context size) you use to compute your statistical relationships matters too. For example, the model may be able to read only 1,000 tokens at a time, or it could be designed to read 60,000 tokens at a time.

As an analogy, the amount of tokens in your input data roughly equates to how many strides you have to take while the size of your context defines the size of those strides.

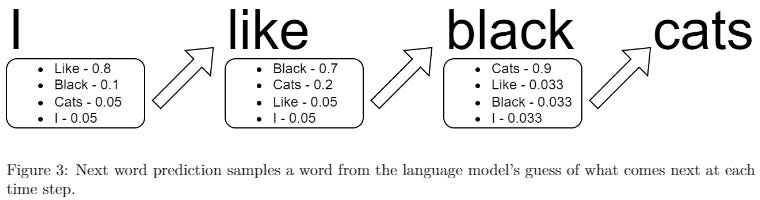

For example, if your context size was only the preceding word, every comparison only requires you to store and process two words of data.5 That’s very cheap but yields a bad model because it won’t understand how a word three words ago matters. This might be why ChatGPT is pretty good but your phone’s autocorrect can be pretty bad. Your phone is only thinking of the likely next word based on the fewer prior words you typed while ChatGPT is considering every word in the sentences/paragraphs you type.

To give an idea of context sizes, GPT-3 had a context size of 2,049 tokens. For GPT-4, this window skyrocketed, ranging between 8,192 and 32,768 tokens. Google’s Gemini now has a context size of one million tokens. A rule of thumb is that there are about 1,000 tokens for every 750 words.

The concept of tokenization can be applied to more than just text. Images, videos, code, and audio can be processed into tokens for multimodal models like Gemini, GPT-4 and Claude. So a one million-token context size means Gemini can, according to Google, process “1 hour of video, 11 hours of audio, codebases with over 30,000 lines of code or over 700,000 words.”6

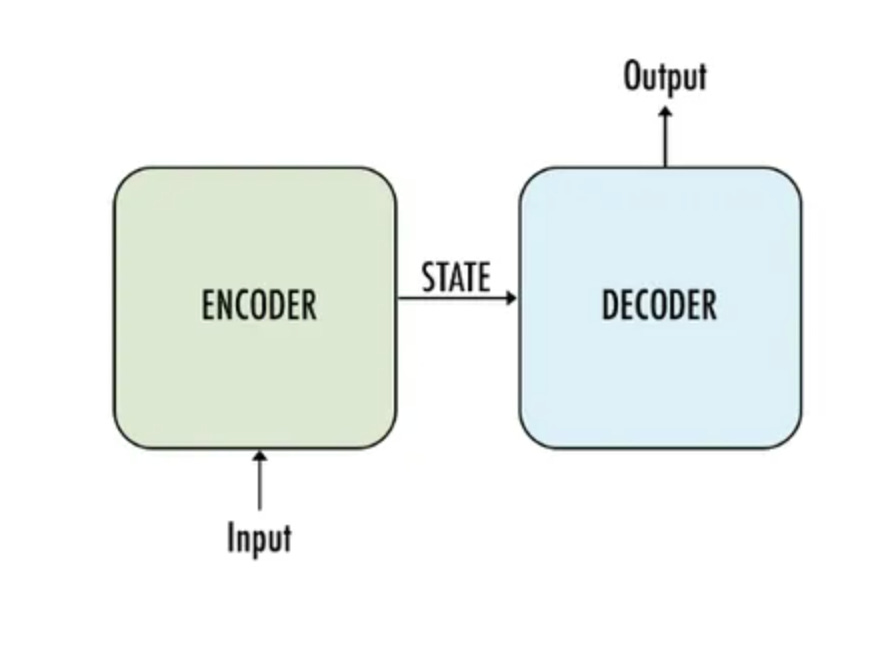

The Model

The most common type of model used to train LLMs is called a transformer. Previously, engineers constructed different models for different tasks (summarization, sentiment analysis, description, etc.), but the transformer architecture unified all those tasks under a single model. Since its development in 2017, the transformer model quickly became the root of GenAI. The encoder (which is less common in more recent models) maps a sequence of the input tokens to a sequence of vectors, then the decoder generates an output sequentially. To go a step deeper, for GenAI, encoders are components that process data, while decoders generate outputs based on that data.

A transformer is a specific type of language model that relies on attention mechanisms. The model allows for more parallelization (as opposed to mere sequentialization) and, like other models, improves its understanding of the input text with each layer. As a result, a transformer is able to analyze entire chunks of text at a time, rather than just one element at a time — and that means it can run faster (taking advantage of GPUs) and process more data, leading to better results!

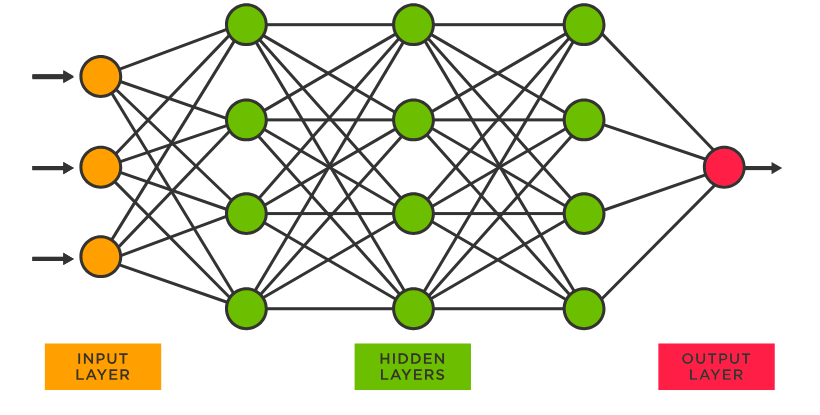

Like other neural networks, transformers are made up of layers. Generally, each layer helps refine the processing of the input so the output makes more sense. Within a transformer, there are two important steps to understand how it works; the first is the “Attention Step” which is when words in one sentence check what other words are nearby and determine which of those words are important. Second is the feed-forward step which is when each word thinks about it and tries to guess what the next word in the sentence should be.

To give an idea of how large LLMs are compared to previous deep learning models, GPT-3 has 96 layers and 175 billion parameters. In contrast, Facebook's Deep Face neural network for facial recognition was only 9 layers and had 120 million parameters.This aforementioned “feed-forward step” is critical in explaining the ambiguity around LLMs and why researchers and scientists cannot be entirely certain how LLMs predict words. In the feed-forward step, the process of predicting the next word of a sentence happens in between the input word vector and the output word vector, and is referred to as a “hidden layer”. This “hidden layer” is named as such because it's in the middle of the model and encodes dimensions that might not immediately map to dimensions we know. This is one of the reasons that LLMs have been hard to understand and why there is a degree of uncertainty regarding how LLMs predict the next word of a given sentence. The size of the model and number of connections further complicates matters.

Though a large language model is a software program, it is not created the same way as most software programs—that is, by human software engineers writing code. Rather, the data is given to a program that tries to predict the next word (i.e., token) in a given sentence, or it tries to fill in the blank, where words from training materials are removed and the model must try to guess what word was there. If the program guesses correctly, then it strengthens its statistical association between the tokens in the sentence. Conversely, if it guesses incorrectly, the association is weakened. This strengthening and weakening is the model “learning.” Because there is no direct human involvement, it’s known as unsupervised machine learning. More specifically, it’s self-supervised learning.

Almost any written material—from Wikipedia pages to news articles to computer code—is suitable for training these models. For example, an LLM given the input “I like my coffee with cream and” will eventually learn to predict “sugar” as the next word because it is able to analyze entire chunks of text at a time. On the other hand, a classic neural network model might analyze the input sequentially, processing one word at a time (“I” before moving on to “like” and so on). Such a simplistic approach quickly forgets the context of the sentence it’s constructing and it becomes less capable of creating coherent paragraphs.

Parameters

The transformer model has parameters (aka “weights”). Parameters are roughly the number of connections between neurons in the neural network. An LLM’s size is measured in how many parameters it has. Each parameter is an adjustable value that describes the strength of the connections between neurons based on the model's performance at predicting text correctly.

A newly-initialized language model will be a really bad prediction because the weighting of each parameter will start off as an essentially random number. But as the model sees many more examples—hundreds of billions of words—those weights are gradually tuned to make better and better predictions. In essence, a model such as this can be considered a refined statistical framework, built to approximate from a dataset it has been trained on.

Fun Fact

Some of the factors affecting performance are the number of parameters, number of tokens (i.e. the amount of data), and the compute (number of computer operations in training as measured in flops). OpenAI estimates that it took more than 300 billion trillion flops to train GPT-3—that’s months of work for dozens of high-end computer chips.

AlexNet, the first model to demonstrate the massive potential of neural networks, had 60 million parameters. Llama 2 has 70 billion parameters. GPT-4 is rumored to have over 10x as many: 1.7 trillion parameters. Going Deeper

In March 2023, DeepMind argued that it’s best to scale up model size and training data together, and that smaller models trained on more data do better than bigger models trained on fewer data. For example, DeepMind’s Chinchilla model has 70 billion parameters, and was trained on 1.4 trillion tokens, whereas its 280-billion-parameter Gopher model, was trained on 300 billion tokens. Chinchilla outperforms Gopher on tasks designed to evaluate what the LLM has learnt.

Scientists at Meta Research built on this concept in February with their own small-parameter model called Llama, trained on up to 1.4 trillion tokens. The 13-billion-parameter version of Llama outperformed ChatGPT’s forerunner GPT-3 (175 billion parameters), the researchers say, whereas the 65-billion-parameter version was competitive with even larger models. Temperature

In AI, 'temperature' is a metaphorical knob that adjusts the randomness in the responses generated by a model. Crank up the temperature, and the AI starts spitting out responses that are more unpredictable, sometimes even quirky or innovative. Dial it down, and the AI's replies become more expected, sticking to the straight and narrow of its training. It’s similar to the difference between jazz improvisation and a classical symphony—both are music, but one is far more freewheeling than the other. Importantly, while temperature adds an element of creativity, it doesn't inherently affect the model's raw performance or accuracy—it simply spices up how the model might express itself. Models as File Compression

Models are essentially a form of file compression (huge corpus of text goes in, a relatively small model comes out). As with most compression, there is some loss. Information is lost as we move from training datasets to models. We cannot look at a parameter in a model and understand why it has the value it does because the informing data is not present.

The way these models are trained is literally through optimizing for reconstruction of the training set. Being unable to perfectly recall everything it’s trained on is known as “information bottleneck.” This is the idea that there's a limited amount of space (in the form of model parameters/weights), and you can’t possibly fully compress all the details in a dataset into the model. It's quite literally like the model is a container and the data is bigger than the container. So what model training is doing is only storing the information necessary to enable for some broad, dataset-level reconstruction.

Even though the model training process is effectively optimizing the model for reconstruction of the training set, we have long known that trying too hard at this actually hurts model performance. That is, you can keep performing training and it gets better and better at reconstructing the training dataset, but, unfortunately, the models that do this aren't really useful at anything other than basically a worse compression algorithm. So, we use a number of techniques to prevent memorization, including messing up the signal a little bit, messing up the data while training, stopping the training earlier, etc.

In sum:

1. A model tries to compress data in a way it can recall the data

2. But it's impossible because there is more data than space to store it

3. But the bottleneck is intentional because it forces the model to make connections between words/concepts rather than just store the data verbatim

4. Because trying too hard to just perfectly memorize data results in worse outcomes than letting the model make its own numerical relationships between words/concepts

Note about authors7

Creating annotated text datasets used to be a core part of the research process, and it's still really important for evaluation. Researchers do create data, and they have training in this, but they don't usually create data that goes into LLMs. Though, their created datasets do get slurped up along with everything else on the web, and this causes problems down the road…

Joseph Stalin’s quote that “Quantity has a quality all its own” could also apply to LLMs. Or, as Ray Bradbury put it, "Quantity produces quality."

The bullet points come from https://www.regulations.gov/comment/COLC-2023-0006-8762

Almost all Dolma information comes from https://blog.allenai.org/dolma-3-trillion-tokens-open-llm-corpus-9a0ff4b8da64

It’s actually a bit more complicated than this. Storing this would still require a giant, very sparse matrix.

It’s far from clear that super large context windows make the LLMs better: Don't get too excited about Google Gemini Pro 1.5's giant context window

The following students from the University of Texas at Austin contributed to the editing and writing of the content of LEAI: Carter E. Moxley, Brian Villamar, Ananya Venkataramaiah, Parth Mehta, Lou Kahn, Vishal Rachpaudi, Chibudom Okereke, Isaac Lerma, Colton Clements, Catalina Mollai, Thaddeus Kvietok, Maria Carmona, Mikayla Francisco, Aaliyah Mcfarlin