I was invited to contribute to an amicus brief for the first time a couple of weeks ago. An amicus curiae brief, meaning "friend of the court," is a legal document submitted by a party not directly involved in a case to provide additional information or arguments that could influence the court's decision. These briefs can highlight relevant issues, express concerns, or offer expertise not already brought to the court's attention by the parties involved. The brief I was invited to was on behalf of the book author plaintiffs suing Meta.

To be sure, I am not a copyright expert. I am also not a law professor. While I teach undergraduate and MBA students about legal issues, including a course on law, ethics, and AI, I have never taught law students. I’m not even a full-time professor. And that made the invitation all the more appealing.

I’ve prided myself on focusing on practical matters. Rather than get lost in the weeds of some esoteric legal theory, I prefer to remain at a level that simultaneously tackles important topics (contract law, free speech, copyright) while applying logic that litigators or in-house counsel could readily use and can be understood by non-experts, like my students. The reasons for this focus can probably be attributed to two sources: I’ve been in-house counsel the entire time I’ve practiced law (where practical application is the coin of the realm), and I think the law should not be mysterious or overly complex (my litmus test is whether my family in rural Missouri can follow the logic). This isn’t to say that many scholars' deeper expertise and theoretical or historical focus is not helpful, useful, or enjoyable. It undeniably is, or at least it can be. It’s just not the niche I prefer.

So, when it came time to draft a brief, two things worked for me: my unfamiliarity with the process and my straightforward approach to the problem.

Whereas another professor more wisely believed our timeframe to complete a brief was perhaps too short, I had no priors to base it on. One morning, I woke up early by chance and used the extra couple of hours before my toddler woke up to read the amicus brief in favor of Meta and then to write what was essentially a legal essay response.

That quick reaction draft, completed in a single sitting, ended up being around seven pages long. Later that day, I was introduced to intellectual property law professors via email who had also expressed interest in writing an amicus brief. I didn’t know any of them personally and had only read a paper by one of them, but I shared my draft. It was only by a stroke of luck that one of the professors who read it was Robert Brauneis, a law professor at George Washington in DC. He happened to be the author of the paper I had read, and coincidentally, we share a similar view of what the most powerful arguments against Meta’s claims of fair use were.

For the next week, he and I took the lead on editing my draft. We reworked some sentences, he added paragraphs here and there, and it started to take shape. A few days in, another professor shared content they wanted to include but was happy to follow our lead because we were already in the thick of it. Bob worked to fold in portions of it. A couple of days later, another professor shared his thoughts and, again, Bob worked to incorporate them. I continued to make some edits and leave comments throughout. At no time did it feel like there were too many cooks in the kitchen. To the contrary, everyone was constructive and supportive throughout the entire process.

Then, while I was attending an AI Forum by the Copyright Alliance and the Association of American Publishers, Bob did the heavy lifting of formatting the document to comply with the court’s rules, adding citations, and otherwise making the brief look less like an essay and more like a respectable legal document. We ended up lopping off two of the five Parts from my original draft and instead added sections restating some law and hammering home points Bob helpfully added.

I’m not sure how many substantive edits other professors made directly to the document. When I shared the initial draft, I gave everyone editor privileges, and we trusted each other when making tweaks. Even minor improvements were helpful and appreciated. I absolutely could not have written a brief as compelling as our final version without the help of the other professors.

I continued to review, make small edits, and leave comments. While I knew the primary audience was the court, I was also aware that journalists and non-lawyers might read it, so I wanted it to be clear, with limited jargon, and with powerful and relatable analogies, metaphors, and arguments.

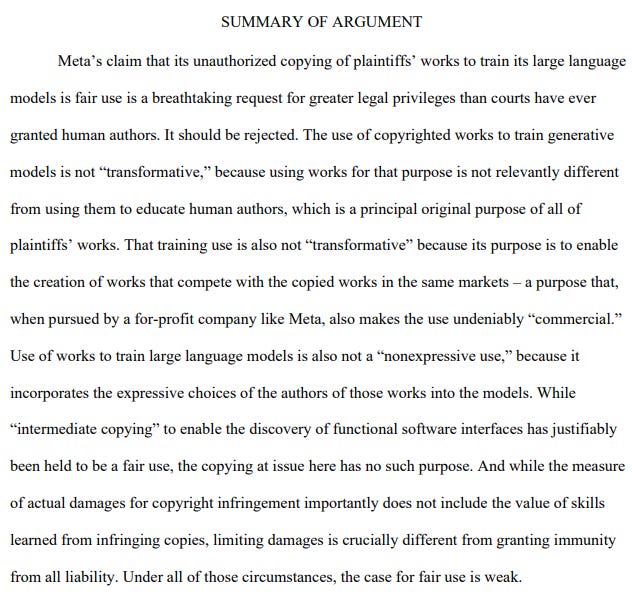

I think we hit the mark, but it’s not really for me to decide. It was a brief written for the legal-minded and the legal-curious. If you believe you’re in either camp, please take a look at the brief and let me know what you think! If you agree that we did well, feel free to shoot the other professors who signed the brief a nice email (we didn’t get paid to write the brief, but kind words are a great substitute payment). If you think the brief is not well-written or the logic is wrong, please let me know! I’d love to learn where we might have blind spots or where I might need to re-think my position.